Next year, Australia will decide whether to accept the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) proposed pandemic treaty, and amendments to the International Health Regulations (IHR). The Australian Government says that these global public health instruments are essential to help us prepare for future pandemics. However, there is mounting concern that the proposed treaty and amendments pose a threat to Australia’s national sovereignty over public health decision-making.

Who runs the world? The WHO will, if Australia and other Member States agree to a proposed pandemic treaty and IHR amendments. This is the view of a growing chorus who warn that Australia risks losing its sovereignty over public health decision-making to the WHO, without necessarily even realising it.

“If we don’t oppose the future IHR amendments and treaty, then based on the current drafts, the WHO will dictate our response to future emergencies,” says Katrina Lane, CEO of community advocacy group Stand Up Now Australia, which is currently running a campaign to reject the WHO’s proposed reforms.

The WHO’s recommendations could include requiring countries to lock down, enforce travel passes and mandatory vaccination, and restrict travel, amongst other recommendations that the WHO’s Member States would be required to implement, says Lane.

But they won’t just be recommendations, they will be requirements. That’s because, “the Australian Parliament will be required to comply with the WHO’s recommendations by passing legislation to bring them into effect,” Lane explains.

It’s this binding and far-reaching nature of the WHO’s proposed reforms that have led One Nation Senator Malcolm Roberts to accuse the WHO of making a “power grab,” and Liberal Senator Alex Antic to coin the phrase, the “WHO d’état.” Concerned citizens have coalesced around groups like Australia Exits the WHO and Stand Up, which collaborate on providing education and activism resources.

A petition voicing opposition to IHR amendments collected 25,000 signatures last month, and a campaign encouraging people to contact their representative MPs has facilitated thousands of calls, letters and emails expressing opposition to the WHO.

Senator Antic says his office “has been inundated with calls and emails from people who don’t want their government to sign them or their children up for a future controlled by the whims of unelected global health bureaucrats.”

However, official sources say this is a storm in a teacup driven by misinformation.

The Director General of the WHO, Tedros Ghebreyesus, strongly denies that the WHO will override national sovereignty relating to future pandemics, calling such claims “fake news” and stating unequivocally that,“no country will cede any sovereignty to the WHO.”

The Australian Government is in agreeance with the Director General’s stance. Responding to questioning on the WHO’s proposed reforms in September, Labor Party Senator Katie Gallagher stated,

“Let me be clear that the proposed treaty will not undermine Australia’s sovereignty in respect to health policy and will not operate to prevail over Australian law. The WHO and the UN have no legal authority to force Australians to take any action, and any negotiated commitments would need to be reflected in Australian laws passed by this parliament for them to become legally binding.”

If it’s that straightforward, then why is there so much pushback against the WHO’s proposed treaty and IHR amendments on the basis that they really do pose a threat to national sovereignty?

Because, “that is what is written in black and white in the documents, and there’s no other way rationally to interpret it,” says Dr. David Bell, a public health physician and former WHO Medical Officer who has written extensively on the WHO reforms and the globalisation of public health more broadly.

“I mean, it’s not a theory. It is very specific in the IHR that countries will undertake to do what a single person, the Director General of the WHO recommends, and it’s repeatedly stated in these amendments.”

It is noteworthy that Dr. Bell references the IHR amendments as the primary source for the claim that the WHO will supersede national sovereignty, while the assurance that this is not the case, made by the Director General and Senator Gallagher, were made in reference to the proposed treaty.

The treaty and the IHR amendments are often discussed interchangeably or in isolation from each other, but they perform different functions that work in conjunction. Here, it is worth pausing to tease them out a bit.

The Australian Government describes both the proposed treaty and the IHR amendments as “major reforms” intended to “strengthen the [WHO’s] role in responding to pandemics.” But while the IHR provides a legal framework for identifying and managing public health threats, the treaty will be more focused on financing, governance,and supply.

The treaty is still under negotiation and will only come into effect if two thirds of the WHO’s 194 Member States vote to accept it. Australia can reject the treaty, but if it is accepted by the required two thirds, the Australian Government advises that it “will be required to domestically implement the agreement in accordance with their constitutional processes.”

The IHRs (2005) are already legally binding, with compliance being enacted through domestic legislation (Australia has already incorporated key IHR standards into domestic law, such as in the Biosecurity Act 2015 and the National Health Security Act 2007).

However, unlike the proposed treaty, acceptance of the IHR amendments only requires a 50 per cent majority. Once the amendments are accepted, individual Member States can reject them within within a designated time frame – otherwise, at the end of this period, the amendments become binding.

This process played out earlier this month, when the deadline for rejecting several IHR amendments (accepted in 2022 and different from those discussed in this article) passed on 1 December 2023. While some countries, like Slovakia, Estonia and New Zealand either rejected or reserved their decision on the amendments, Australia simply did nothing. This means that the amendments have now come into effect for Australia.

Understanding how acceptance of and compliance with the IHR is enacted may shed light on Senator Gallagher’s statement, that, “The WHO and the UN have no legal authority to force Australians to take any action, and any negotiated commitments would need to be reflected in Australian laws passed by this parliament for them to become legally binding.”

“To fulfil that, one of two things would have to happen,” says Dr. Bell. “Australia would have to opt out of the IHR amendments. You can say we will not take part in these IHR amendments and then the old IHRs will apply. Or, Senator Gallagher fully has the intent of changing Australian law to allow the WHO to have control, when the WHO chooses, over the healthcare of Australians. It’s either one of those two.”

Katrina Lane, CEO of Stand up Now Australia, suggests a third explanation for Senator Gallagher’s denial that the proposed WHO reforms will be legally binding despite clauses to the contrary – incompetence.

“Key members of the committee responsible for public consultation and review of the [recently accepted] IHR amendments have admitted that they didn’t even know they’d signed off on them,” says Lane, who can only share this information on the proviso of maintaining anonymity of the committee members in question.

To wit, the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties’ (JSCT) review of the 2022 IHR amendments are buried in a report titled, Timor-Leste Cooperation in the Field of Defence and the Status of Visiting Forces.

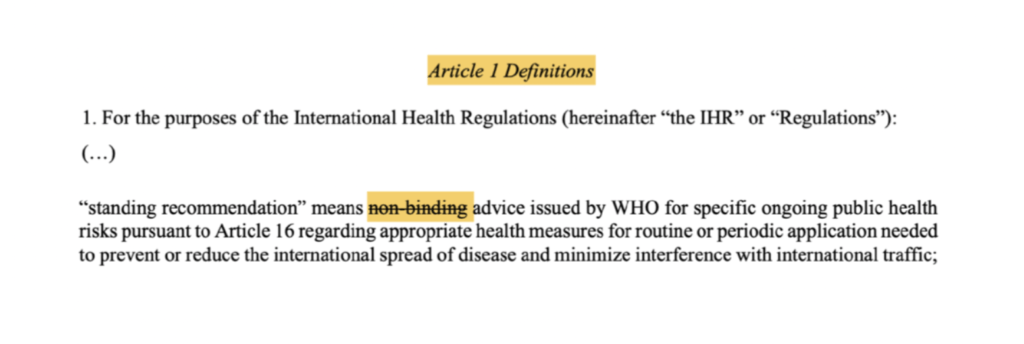

The significance of the proposed IHR amendments centres on the upgrading of the WHO’s Standing Recommendations, which have until now been non-binding under IHRs, to become binding. This is why Dr. Bell refers to the amendments as “the “teeth of the WHO’s proposed reforms.

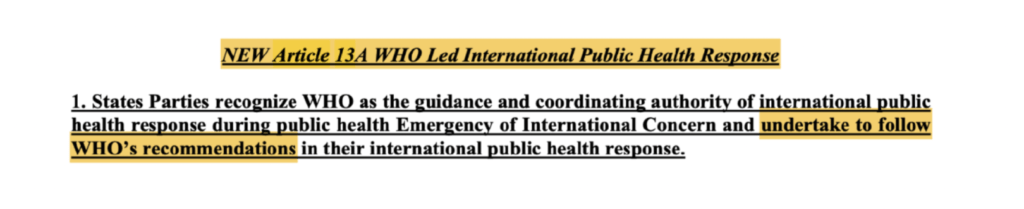

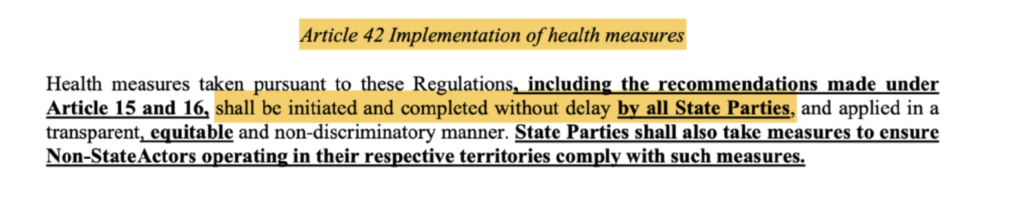

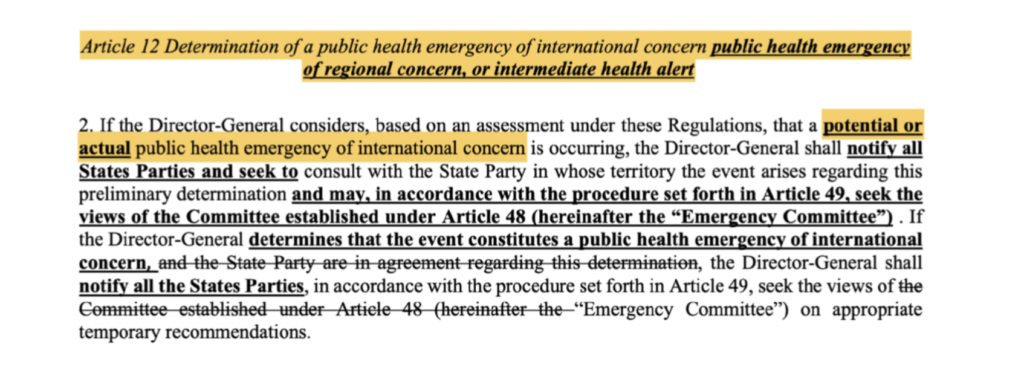

Assuming Australia accepts the 2024 IHR amendments (which would only require that Australia fails to reject them by March 2025), we will be required to “undertake to follow WHO’s recommendations in [Australia’s] international public health response” (Article 13A), which will need to be “initiated and completed without delay” (Article 42). In case anyone is still circumspect about the binding nature of these recommendations, the words “non-binding” have been struck out from the definition of a “standing recommendation” (Article 1).

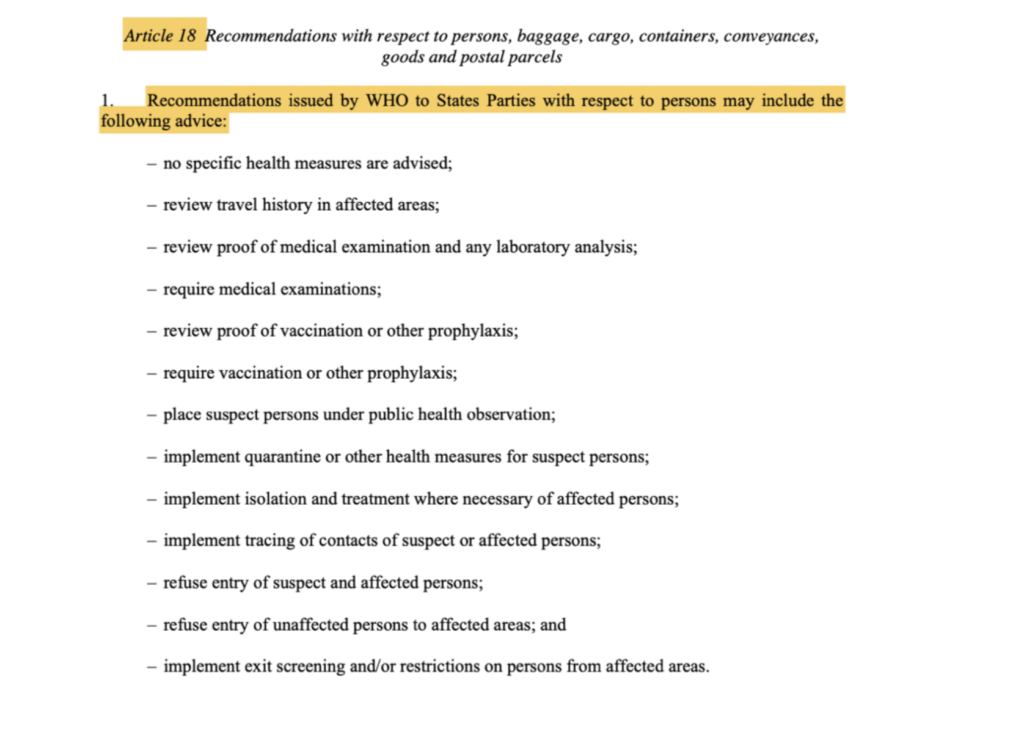

When taken with Article 18 of the IHR, which states that the WHO can recommend such actions as requiring medical examinations, require vaccination and proof of vaccination, quarantine measures, isolation and treatment of affected persons, contact tracing, and travel restrictions, amendments that change the nature of such recommendations from ‘opt in’ to legally binding is no small matter.

Moreover, Dr. Bell highlights that these recommendations can apply to any situation where the WHO Director General declares a perceived threat of a public health emergency, even in the absence of absence of demonstrable harm.

This broadening of IHR to apply to “potential” threats to public health as well as “actual” threats (Article 12) raises questions of how far the WHO’s binding recommendations will reach, should the amendments be accepted.

“Under the WHO’s ‘One Health’ policy – which covers health of humans, animals plants and the environment – it’s possible that the WHO will be able to make recommendations about perceived emergencies related to just about anything, not just pandemics,” says Lane.

This is a key concern for Senator Antic. “I’m worried that this is another step in heading us towards the likes of climate lockdowns, which are not in the realm of conspiracy theory any longer. I think we’re going to see a time where they become the stuff of reality,” he says, noting that climate change is increasingly being positioned as a preeminent global health concern in government and peak body reporting.

Regardless, even if the IHRs were to apply only in the case of perceived pandemics, we can expect more emergencies of this nature to be declared as a result of the “huge surveillance program” set out in the IHR amendments, says Dr. Bell.

Indeed, the Australian Government specifically states that the proposed IHR amendments relate to “core capabilities set out in the IHR relating to surveillance, monitoring, reporting, notification, [and] verification,” of pandemics.

“They are setting up a huge mechanism, which is using our money to find viral variants … which will absolutely find viral variants, because that’s nature,” says Dr. Bell. “This will then be used to lock people down and then extract wealth from them through a vaccine, a 100-day vaccine, in order to give them their freedom back for a while. And that is the sort of life that they are explicitly laying out and talking about…So then the question is, is that a good thing or a bad thing?”

Unsurprisingly, groups like Exit the WHO and Stand Up are of the opinion that this is a bad thing. “The WHO is an advisory body,” says Lane. “We didn’t elect them to represent us, and they have a broad-brush approach to medical situations that require nuanced solutions which a global body can’t offer,” she says, adding, “We are perfectly capable of governing ourselves.”

Senator Antic is more forthright, stating that “Australia should immediately withdraw” from the WHO. “Australia is a sovereign country that should be making sovereign decisions about its own healthcare.”

Politicians from around the world are increasingly taking a similar view. In recent months, leaders from the European Union, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Estonia, South Africa, the Philippines, and the US have tabled bills and written letters opposing the WHO’s treaty and amendments.

Whether Australia chooses to accept the WHO’s proposed reforms or not, Dr. Bell says we need to “stop pretending” that the reforms will not result in the ceding of national sovereignty over public health decision-making to the WHO.

“If people want to have the freedom to visit their families, to travel and to make those sorts of choices for themselves rather than someone completely disconnected from them, someone even in another country making those decisions for them, then they should be worried about this,” says Dr Bell.

Ultimately, he says, “If you value your way of life – then you have to oppose these sorts of things.”

The Department of Health was contacted for comment but did not respond by publication deadline.