A deep dive into the research informing the Australian Government’s proposed misinformation laws reveals flawed logic driving bad policy. The assumption that ‘the government is always right and everything else is misinformation’ pervades academic research, leading to circular definitions being baked into legislation and digital platform policy. The inevitable outcome is censorship of content that contradicts the official position – a scenario that will predictably manufacture public consent for the policies of the government of the day.

The Australian Government is currently reviewing public submissions on its proposed new laws to combat misinformation and disinformation online, as covered by Umbrella News when the draft legislation was first tabled mid-year.

If passed, the bill will considerably expand the Australian Communication and Media Authority’s regulatory powers over digital platforms, forcing platforms to comply with codes and standards devised by ACMA to counter misinformation and disinformation (at the moment, adherence to the Australian code is voluntary).

But a look at the research underpinning the legislation shows that ACMA’s bill is based on a series of logical fallacies and unsupported assumptions, calling into question both the need for the proposed laws, and whether any good can come of them.

The most glaring logical fallacy is the assumption that the official position is always the ‘true’ one. In a study of COVID misinformation in Australia during the pandemic, commissioned by ACMA, researchers from the University of Canberra categorised beliefs that were contradictory with official government advice as ‘misinformation’, regardless of the accuracy or contestability of the advice.

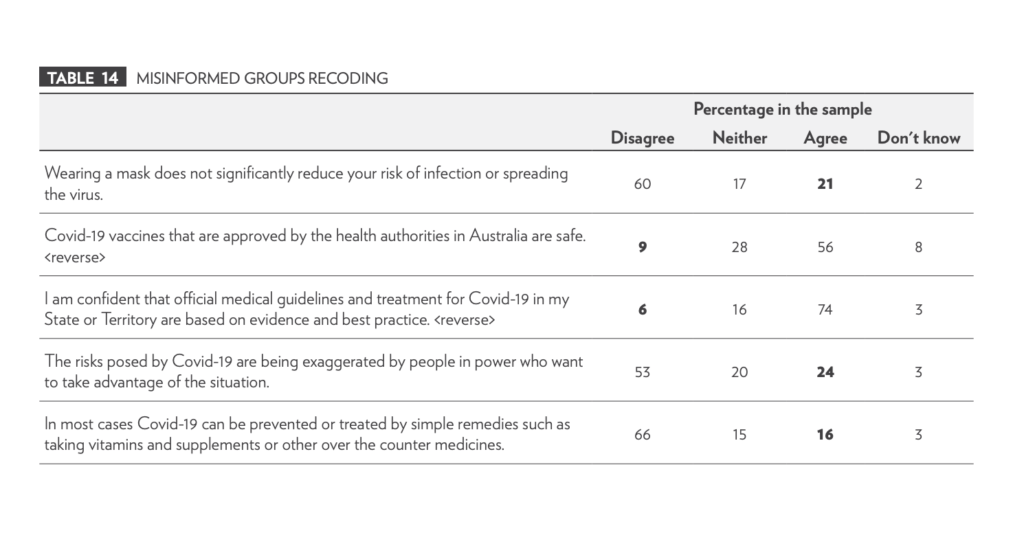

For example, respondents were coded as ‘misinformed’ if they doubted the efficacy of masking in limiting virus transmission, if they thought that the COVID vaccines were unsafe, or if they believed that COVID could be treated with vitamins or supplements (e.g.: Vitamin D).

These positions are supported by peer-reviewed scientific literature but are in opposition to official government/health authorities’ advice. It is obviously incorrect to categorise these respondents as misinformed. What the researchers really meant is that these respondents believed information that contradicted the official position.

Another study commissioned by ACMA, by creative consultants We Are Social, makes the same error. The researchers classify ‘anti-lockdown’ content as a ‘misinformation narrative’, despite several cost-benefit analyses of Australia’s lockdowns finding that they caused significantly more harm than any benefits afforded.

Based on these studies, ACMA states that, “Belief in COVID-19 falsehoods or unproven claims appears to be related to high exposure to online misinformation and a lack of trust in news outlets or authoritative sources.”

This claim is unsupported by their own research, which instead shows, ‘Belief in positions contradictory to the official position appears to be related to high exposure to alternative viewpoints and a lack of trust in news outlets or authoritative sources.’

ACMA’s faulty logic is baked into its misinformation bill by the explicit exclusion of content produced by government, accredited educational institutions, and professional news from the definitions of misinformation and disinformation.

This is a departure from the traditional definitions for misinformation and disinformation, which encompass all information that is false or misleading, either unknowingly (misinformation) or with the intention to deceive (disinformation), and do not exclude information/content based purely on its source.

ACMA offers no rationale for excluding some sources of misinformation from its proposed regulatory powers, but not others.

Alongside these definitional problems are ACMA’s claims that its proposed laws are necessary because misinformation and disinformation are becoming more pervasive and will cause harm. Once again, ACMA’s research does not support its claims.

ACMA doesn’t actually know how much misinformation there is. A report explaining the research and rationale behind its bill states that, “the true scale and volume of misinformation in Australia is currently unknown.”

Moreover, reports of misinformation have been conflated with actual misinformation. ACMA references “increasing concern” about misinformation online, measured by survey respondents reporting how much misinformation they believe they have seen.

But don’t we all know that “correlation is not causation,” as we have heard ad nauseum when it comes to reports of physical harms on pharmacovigilance databases associated with vaccines?

Conflating subjective user reports with actual instances of misinformation and online harm is common in government and peak body reporting in this field. Researchers should demonstrate that perceptions of an increase in misinformation online, and perceptions of resultant harm, correspond with an actual increase in misinformation and harm, but often don’t.

Conditions that may give rise to an increase in reports of misinformation and harm include increased social sensitivity, better promotion of reporting tools, and the impacts of cultural developments (e.g.: political polarisation).

Similar to Mean World Syndrome, where people perceive the world to be more dangerous than it actually is due to prolonged exposure to bad news and/or violent content, perceptions of an increase in misinformation may also be the result of hypervigilant users being primed to be on the lookout for such content.

Then there is the quantification of harm. The ACMA report refers to several case studies to demonstrate how misinformation and disinformation cause harm, but falters on the first by getting key facts wrong. ACMA attributes the unrelated deaths of several people who died of natural causes to the January 6th riot at the US Capitol, raising questions about ACMA’s ability to reliably discern true information from misinformation.

A second case study refers to research showing that anti-vaccine content (even if true and accurate) can sway people’s vaccination intentions. Does this cause harm, or save lives? The report doesn’t offer evidence for either.

A third case study on the real-world impacts of anti-5G content makes a more convincing demonstration of resultant fiscal harm, but it is unclear how the proposed measures in ACMA’s bill will prevent such harm.

There appears to be an inherent assumption that online censorship of certain information will reduce harm, but current research shows that censorship simply encourages users to find work-arounds, a fact acknowledged by ACMA in the report.

So far, so hazy, but the real-world consequences of basing legislation on a quagmire of fallacious assumptions are crystal clear.

The exclusion of information from government, approved institutions and the press from the regulatory reach of the bill, coupled with the assumption that misinformation and disinformation (from non-government or non-institutionally approved sources only) can cause a broad range of harms, implies practical application that looks something like,

‘The policies of governments and peak/governing bodies save lives and are intrinsically good for the nation, or the world. Therefore, any information counter to these policies threatens lives and causes harm.’

When adopted in the marketplace, policies underwritten by such logic read like YouTube’s medical misinformation rules, which categorise as misinformation any information that, “contradicts local health authorities’ (LHA’s) or the World Health Organization’s (WHO) guidance about specific health conditions and substances.”

As journalist Michael Shellenberger has pointed out, if YouTube had existed over the past 200 years, then under such a policy they would have banned criticisms of bloodletting, thalidomide, lobotomies, and sterilising the mentally ill, all of which were recommended by official health authorities at one point in time.

Imagine if YouTube had been around over the last 200 years.

— Michael Shellenberger (@shellenberger) August 16, 2023

It would have banned criticisms of blood-letting, thalidomide, lobotomies, and sterilizing the mentally ill, all of which were recommended by official health authorities.

The impacts of such policies extend beyond public health, to all manner of civic and political issues from energy policy, to environmental issues, to elections.

In the latest Australian news cycle, Meta-affiliated fact checker RMIT FactLab was exposed for misusing its position to censor the government’s political foes on the issue of the Voice referendum. Biased fact checkers at RMIT targeted anti-Voice content, labelling as false or misleading content that ran counter to the government’s Yes campaign, even if demonstrably legitimate. In a rare case of retribution, Meta has since suspended its partnership with RMIT FactLab.

In the US, new research linking wind industry developments to damaging environmental impacts (threatening the extinction of the North Atlantic right whale) has been labelled as false on social media platforms, propped up by fact checks and media coverage heavily funded by the wind industry and reliant almost entirely on government information.

These are but a few examples of a global trend in the way that governments, think tanks and industry are partnering to advance their mutual interests at the expense of valid and necessary expression – a phenomenon called the Censorship Industrial Complex, and one that fits the classical definition of Fascism.

When views that run counter to the official position are delegitimised with misinformation labels, suppressed in reach or removed from digital platforms entirely, users are not able to access information offering a range of views outside of the government’s preferred narrative.

This has the potential to influence public opinion in favour of the government of the day’s position on any number of issues. Pause to consider that, whether now or in the future, you will at some point be ruled by a government that you disagree with on a good many things.

Unfortunately, the aforementioned studies and report that ACMA uses to justify its misinformation bill are not outliers. Misinformation researchers frequently treat the official position as the right one, lumping genuine scientific debate into the misinformation basket. In doing so, researchers inadvertently prove that policing misinformation is much more difficult to do than reductive government policy statements would have us believe.

Last month, misinformation research reached a nadir of self-referential absurdity when a study condemning physicians for spreading COVID misinformation turned out to be absolutely riddled with… misinformation.

Researchers from the University of Massachusetts misleadingly stated that the J&J COVID vaccine was the only one associated with deaths, and used an incorrect figure for the tally of COVID deaths. They coded numerous scientifically supported claims as ‘misinformation’ including: that the vaccines are not effective at preventing transmission; that natural immunity is equal to vaccine immunity; that it is possible that the virus may have originated in a lab; and that masking is associated with harms.

Astute readers have probably guessed by now that the main problem lies in the researchers’ definition of misinformation, the wording of which is remarkably similar to YouTube’s medical misinformation policy:

“We defined COVID-19 misinformation as assertions unsupported by or contradicting US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance on COVID-19 prevention and treatment during the period assessed or contradicting the existing state of scientific evidence for any topics not covered by the CDC.”

If the CDC were always right, this might have worked out well. However, a preprint detailing 25 statistical and numerical errors shared by the CDC during the COVID pandemic shows that official bodies like the CDC are also prone to propagating false and misleading information.

That the study was published in the Journal of the American Medicine Association (JAMA) highlights that just as misinformation researchers, government report writers, and official health bodies are fallible, so too are peer reviewers.

Sweeping new laws proposed (and in some cases already implemented) in the EU, Ireland, the US, Brazil, and now Australia would have people who can’t even produce a report free of misinformation decide what people can and can’t say on the internet.

Yet clearly, a top-down model of information control managed by fallible people and agencies is not a satisfactory solution to the problem of misinformation – a problem that has not yet been properly defined by the government agencies seeking to solve it.

The Australian Government would be wise to abandon its hopelessly flawed misinformation bill entirely, and should instead seek to answer the question arising from its research: why do so many Australians no longer trust official government advice?