Two years of Covid19, six lockdowns and numerous restrictions left many Victorians feeling hurt and isolated. For those who decided against being vaccinated, those feelings were magnified.

Worried about the toll this had taken on those around her, Belinda Bernardini, from the outer Melbourne suburb of Chirnside Park, decided to do something about it.

Targeting the nearby suburbs of Croydon and Lilydale as well as Chirnside Park, she set about reconnecting people who Bernadini says she started helping people who were ‘struggling,’ establishing health and gardening groups that welcomed all, whatever their views on the response to the pandemic.

This year, Bernardini moved them into a larger group, My Place Yarra Valley, taking her lead from the suburban network that has developed since the first My Place group was established in Frankston. Its focus is still community engagement, but now through scrutinising the activities of the local Yarra Ranges Council.

It was while looking over the agenda for a council meeting late last year, that Bernardini noticed an issue that has since drawn people to council meetings in the Yarra Valley and beyond.

“I came across a webinar while looking into the Monbulk UDF,” she says, referring to the council’s plans for an Urban Design Framework (UDF) in the neighbouring suburb of Monbulk. Those taking part were discussing the 20-minute neighbourhood concept.”

What she had come across is a global programme endorsed by the Victorian government – to maximise local use of urban spaces as much as possible and to ensure they can be reached on foot or by bike within a maximum of 15 or 20 minutes.

The webinar Bernardini saw was streamed two years ago and features Jeremy Mant, who leads the 20 -minute neighbourhood policy and implementation at the Victorian Department of Transport, explaining the advantages of 20-minute neighbourhoods: greater local access to daily needs, more urban density or ‘nearness,’ less traffic, less pollution and generally healthier living.

For Mant, the concept is the underlying principle of Plan Melbourne 2017-2040, a blueprint for future urban development, not just in the city itself but across the state metropolitan areas. Importantly, it is “really based around looking at global issues as well’ and in this context, he links the plans to UN Sustainable Development Goals.

That the 20-minute city is linked to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals suggests to Ms Bernardini that there may be some sort of top-down global imposition exercised through the Victorian government.

“I wrote to local state MPs asking ‘Can you please explain why we are implementing a UN agenda now?’ But I have had no reply. Why I don’t know.”

But it was the concept of ‘nearness’ or urban densification that initially pricked Ms Bernardini’s attention.

“What struck me after watching this was that they were discussing how to ‘sell’ the 20-minute neighbourhood concept using words such as ‘don’t discuss densification just talk about ‘nearness’. I found this manipulative dialogue, and that immediately made me ‘question’ the concept”.

Whether 15 or 20-minute neighbourhoods, such concepts are by now a source of global controversy. Since October 2022, when the English city of Oxford announced it would apply traffic filters in its city centre as part of its plan to become a 15-minute city by 2040, the issue has been subject of growing concern among community groups.

Paris isn’t the first city to champion a “city of short distances,” with hyper-proximity. Melbourne has been planning “20-Minute Neighbourhoods" with shops, parks, schools, medical assistance, etc. all within a 20 minute walk, bike or transit ride. V/@wef pic.twitter.com/WVx9vmJESF

— Brent Toderian (@BrentToderian) January 25, 2020

What some see as plans for sustainable development and improved convenience, others view as a threat to personal liberty, freedom of movement and an extension of government control. Almost as quickly as protests began, they were labelled as based on yet another conspiracy theory.

According to Belinda Bernardini, such a response says more about those making them than those targeted. “Being called a ‘conspiracy theorist’, an ‘anti-vaxxer’ or a ‘cooker’ is what people say when they have no real argument to back up what it is, they are trying to discredit.”

Like most critics of the 20-minute neighbourhood scheme, she is worried about the potential impact on personal freedom. “I believe these neighbourhoods create a mechanism for the curtailment of liberties and freedoms,” she says. “It wouldn’t be difficult for any current or future government to implement policies or mandates that limit the use of vehicles in certain areas, during certain times on certain days. It could even implement a carbon credit system. In Birmingham, they are issuing ‘Clean Air Zone’ fines, which remind me of the Covid fines handed out in Melbourne.”

The spectre of the pandemic and lockdowns also loom large over concerns about the 20-minute city. The repeated mention of Covid-19 during the webinar was enough to spark Ms Bernardini’s concerns.

“COVID was raised several times during the webinar, along with lockdowns. I thought to myself ‘Why are they discussing this? Why is this an issue? We aren’t in lockdown, and COVID is a one-in-100-year event… why do we even need to be concerned about being ‘near to things’ when we are no longer in lockdown and hope never to be in a lockdown again?”

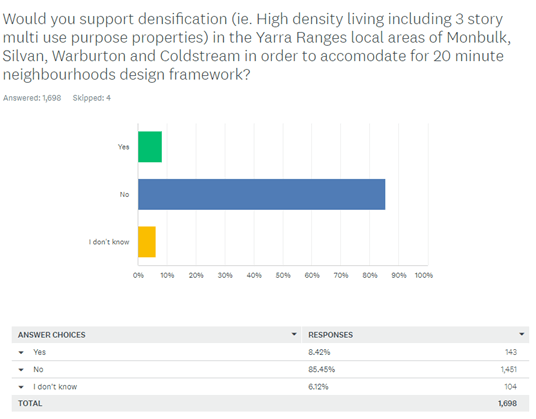

She says that a survey she initiated confirms her view that by far the majority of people living in the districts administered by the Yarra Ranges Council do not support, in particular, the high-density housing aspect of the 20-minute city plan. Local polling showed the following results:

Ms Bernardini’s concerns – and references to the UN’s SDG program – were submitted by My Place members to the December 13, 2022, council meeting. With an extended break for Christmas and New Year, however, the council didn’t meet again for six weeks, by which time news of the Monbulk plan had spread through the community.

When the council reconvened on January 31, 140 people were sitting in the public gallery, not the half dozen local stalwarts who usually attend council meetings. Exchanges between members of the public and councillors over the Monbulk plan became so heated that the mayor, Jim Child, called in the police and closed the meeting to the public.

“Due to the safety of councillors and staff, I felt I had no other course of action,” Mr Child later explained.

“Police were called to assist with the crowd of 100+ agitators, who didn’t follow the rules we set down for council meetings. Sadly, this had an unfair impact on those who did. I’d like to thank the police who assisted with the crowd and ensured that people left the council meeting safely.”

Bernardini concedes that a small number of attendees were unruly but says they weren’t from My Place Yarra Valley and that everyone remained seated. She says My Place members were invited to a private meeting with the council the following Monday and that relations between the parties are good.

However, frustrations remain over the council’s involvement in the 20-minute neighbourhood plan. According to Bernardini, “I guess what we have an issue with is a governance process that I believe is fairly undemocratic. It doesn’t really allow for good dialogue between council or councillors and the community.”

For his part, Mayor Child remains committed to the Monbulk UDF. “The concept behind 20-minute neighbourhoods is simple – communities are designed to make sure everything you need day-to-day is close to home and a walkable distance away,” he said. “The intent is for people to be able to move about easily and freely without being burdened by excessive travel or costly transport options. It improves movement and access, rather than preventing it.”

Mr Child says the introduction of such schemes in suburbs originally designed around car use is why long-term urban design planning is needed. For Bernardini, such concepts as the 20-minute neighbourhood might be suitable for the inner city, but she is sceptical as to why they are being proposed for Monbulk, an outer suburb that is not projected to undergo significant growth.

“I can see how a young person who lives in Brunswick would love the concept. I’m not saying that the concept doesn’t have merit. What we’re saying is that it doesn’t have a place in Monbulk.”

The role of SDGs in the planning process is still unclear. For Damien Closs, Acting Director of Planning and Sustainable Futures at Monbulk, the 20-minute cities plan “does not directly reference the UN sustainable development goals”. For his part, Jeremy Mant, Director of the 20-minute planning process in Victoria, “it is really about global to local – this is a typical real, local addressing of UN goals”.

Bernardini and other My Place members have maintained their council meeting presence while also letterboxing their arguments. “I regard myself as a critical thinker who challenges the narrative and has a healthy distrust of the government,” she says.

“Assume nothing, question everything.”